Lucky 7: Erica Podwoiski

“While I don’t always achieve it, I continue to strive for this quality, a subtle fuck-you to misogyny, patriarchy, censorship, narrowly defined gender expectations and any attempts to shame or demonize women who enjoy sex and aren’t ashamed to make art about it.”

Erica Podwoiski is as much of an erotic philosopher as she is an erotic artist.

Her work is deeply personal; a clear result of the use in her own source material to create her paintings, drawings, and cyanotypes. This technique allows her to control the subjects of her pieces and allows them to seek pleasure rather than hiding behind taboos imposed on us by modern American sexuality.

Her positive perspective on sexuality shines through her work while her openness to have conversations about how sex fits into the grand scheme of life creates a sense of inherent community we so desperately need.

I enjoyed finally getting to meet Erica in person and seeing her amazing work at In The Flesh (I know. How many times are we going to mention this show? One more time after this interview …at least)

I’m also super excited to collaborate with her in the future. Enjoy this look into Erica’s journey and her approach to her deeply erotic work.

1. What’s your name? - Where are you from? - Where are you now? Who are you—philosophically, ethically, artistically, sexually?

My name’s Erica Podwoiski. I grew up in Garden City, Michigan, a small suburb of Metro Detroit and proud home to the world’s first K-mart. I’ve been living in Boulder, CO since 2014, when I left my home state to pursue an MFA in Painting & Drawing at CU Boulder.

As a creator, I’m committed to promoting a culture of sexual empowerment and radical vulnerability. I make paintings, drawings, and cyanotypes that embrace the sensual and abject aspects of the body. When I’m working with erotic themes, I allow my desires to function as my guide. If something turns me on I try to write it down, draw it, or photograph it immediately. This is one of my more annoying habits; when my partner is in a particular pose that I find enticing, I’ll reach for my camera phone. He’s like a sexy Jesus with his long hair and lithe physique, so it’s hard for me to control myself. In the years that we’ve lived together, he’s become both my artist assistant and the consummate muse.

I prefer full control over my source material, so I typically draw from personal photographs and video stills of intimate encounters. Rather than ignoring or concealing parts of the body that may cause unease, I seek out the taboo. By asserting ownership of my body within my images, I aim to open up conversations around the representation of women and sexuality in contemporary American culture. The figures in my art leer back at the viewer, seek pleasure without shame, and rage against the demure.

Politically, I most identify with anarchist principles like those espoused by the late activist and anthropologist David Graeber. I believe that people are essentially good but that the systems and institutions we live within are fundamentally fucked. Like Graeber, I’m hyper-critical of neoliberalism and capitalism’s relentless pursuit of profit over the health and longevity of our planet.

I’m an advocate for complete bodily autonomy, which includes full access to abortion and comprehensive healthcare for all, including those seeking gender-affirming care. I believe that access to pleasure is a fundamental human right. The writings of Audre Lorde, Anaïs Nin, bell hooks, and Georges Bataille have all informed my views on eroticism and love. I believe in love above all else, however cliched that may sound!

Sexually, I identify as straight but fluid. I love a little gender fuckery, and I enjoy playing with power dynamics in the bedroom. Switching between dominant and submissive roles is exciting to me, and I think this comes through in some of my art. I’m pretty open when it comes to trying new things, and I agree with Anthony Bourdain’s sentiment when it comes to the body. He says, “Your body is not a temple, it’s an amusement park: enjoy the ride.”

2. How did your household/groups outside of your home treat the topic of sex and eroticism when you were growing up? How do you think that informed your view on sexuality in your life and in your art?

I feel very lucky to have been raised Heathen; religion was not a part of my upbringing. My parents were agnostics who valued science, the arts, justice, and love above all else. When I was four, I asked my mom where babies came from, and she gave a very straightforward and matter-of-fact explanation.

Sex and eroticism were not treated as taboo; we had poster reproductions of Dali’s surreal nudes of Gala and a large framed print of Matisse’s “Le bonheur de vivre” in the living room. Some of my friends would get all bent out of shape over the naked women in that Matisse painting, and I never understood why. In our household, nudity in art was no big deal, and I carried that attitude into adulthood.

Growing up, I always felt that I could be myself around my family, which is saying a lot because I was a little weirdo. As a kid, I had an intense crush on the cartoon character Mr. Ratburn from the book series “Arthur” (the Aardvark). I’d make little drawings of his character and cut them out with scissors and hold wedding ceremonies with my drawings of Mr. Ratburn. After I lost interest in the rat, a string of attractions followed, including but not limited to a host of neighborhood boys, the cartoon Disney Aladdin, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Tim Curry. Through it all, I was never shamed for my wild fantasies and desires. If anything, I was enabled by relatives like my grandma, who sewed me elaborate Disney princess costumes and a wedding dress, which I wore to my wedding with Mr. Ratburn.

Later, when I started dating real boys, my folks weren’t overprotective. I was strongly encouraged to use contraceptives, but that was the extent of my education. In high school, my mom had a rule about “leaving the bedroom door open,” which was her well-intentioned attempt to exercise some parental discretion. That just led me and my boyfriend to fool around in the car at the empty Century 21 Real Estate parking lot down the street. I had the autonomy to explore my sexuality and art as a vehicle to express myself. Without those conditions, I’m not sure I’d be making the art I make today.

3. Was art always something you wanted to pursue?

As a kid, art was like breathing; I was always drawing. “Cat people” were my earliest preoccupation, and I was very fortunate to have parents who were genuinely engaged and supportive of my artistic obsessions.

My family and I were regulars at the Detroit Institute of Arts and all the local art fairs. Both my parents were creative people who chose more “practical” paths in life (my dad became an electrical engineer, and my mom worked in retail and later as a makeup artist for Estée Lauder). I think they truly understood how important art was to me, so there was never any pushback when I decided I was going to be an artist. I don’t even recall a decision being made. It was all I ever wanted to do.

4. What has the evolution of your work looked like? When did you start exploring erotic subject matter?

In High School, I had two amazing art teachers, Mrs. Rapin and Ms. Mitoraj, who founded a weekly drawing practice called “Figure Friday.” Without funding for life models, us kids would take turns modeling for each other on tabletops once a week. We posed in prom dresses and kilts, the boys often removed their shirts, and our teacher kept a wary eye out for any potentially square intruders in the hallway. The whole operation felt mildly subversive, and completely invigorating, and managed to set the tone for my ongoing obsession with the body.

I did my undergrad at a small art school in Ohio called the Columbus College of Art & Design, where I continued to focus on figure drawing and painting. During my junior year, I took a life-altering course called Feminist Art History that introduced me to artists like Joan Semmel, Renee Cox, Betty Tompkins, and Tracey Emin. It was the first time I’d heard of these artists, which was simultaneously enraging and galvanizing. Before that class, I worried that I’d be seen as narcissistic, or that I wouldn’t be taken seriously if I made art about sex or myself.

Learning about this rich history of female-identifying artists- many of whom drew from their own bodies and personal experiences to make art- gave me the permission I needed to move forward. I got to work on a large painting of myself on the receiving end of cunnilingus and never looked back though I did offend a local passerby so thoroughly while I was transporting the cunnilingus painting to my studio that they called the president of CCAD (the late and great Denny Griffith) to complain of indecency. He told the individual to chill out and reminded them that it was an art school!

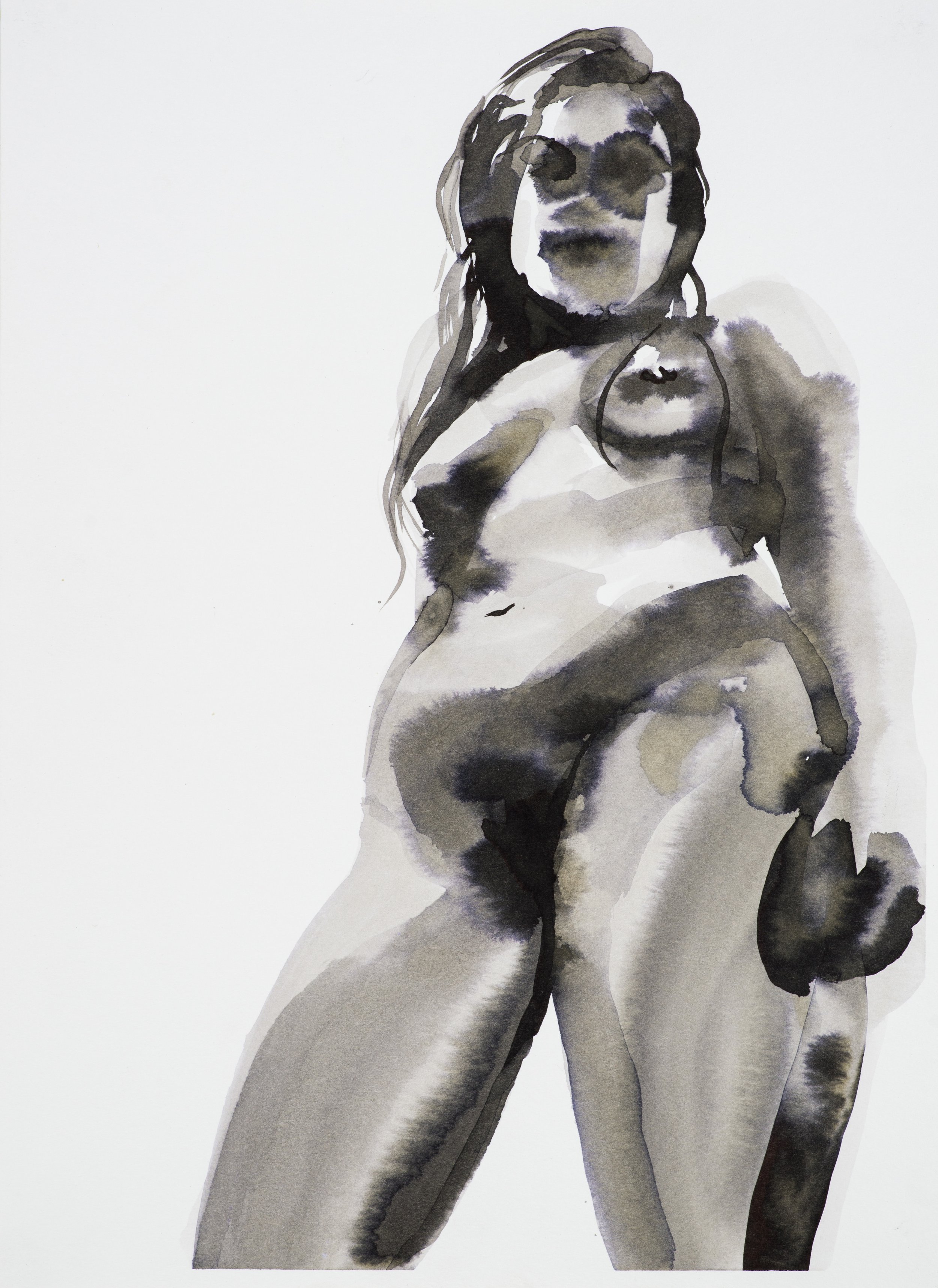

During the tail end of my residency in the MFA program at CU, I experienced a major shift in my approach to painting when I started working in ink. Previously, I’d been making pretty tight, representational oil paintings that left little to the imagination. I started experimenting with ink in a film class taught by Erin Espelie. We were asked to create a visual response to something we watched in class, so I chose Carolee Schneemann’s experimental 1967 film “Fuses”, which featured collaged and hand-painted shots of Schneeman and her lover James Tenney engaged in various intimate activities. It was a gorgeous film told from Schneemann’s perspective, and I loved the mysterious quality of her imagery.

Drawing from my own erotic documentation, I started a series of gestural inks, giving myself a limit of 8 minutes to work on each piece. At the time, I was married to my High School sweetheart, but I knew we were on the precipice of divorce. These inks felt like a last-ditch effort to capture the tenderness that still existed between us. The immediacy of the approach was also a stark contrast to my previous process, which required weeks or months of work on a single painting with little chance of surprise. Ink blurred and obscured my images in ways that were beyond my control, often resulting in images that surprised me.

When I shared my nasty inks with my professor, Erin Espelie, she was wholly supportive, referring to one of the penis inks as a “nighttime forest” and “a subtle fuck-you”. While I don’t always achieve it, I continue to strive for this quality, a subtle fuck-you to misogyny, patriarchy, censorship, narrowly defined gender expectations and any attempts to shame or demonize women who enjoy sex and aren’t ashamed to make art about it.

5. Pick a piece of your work and tell us about it. What was behind the concept of this piece? What story are you trying to tell? Did you like it when you published it and do you still feel the same way?

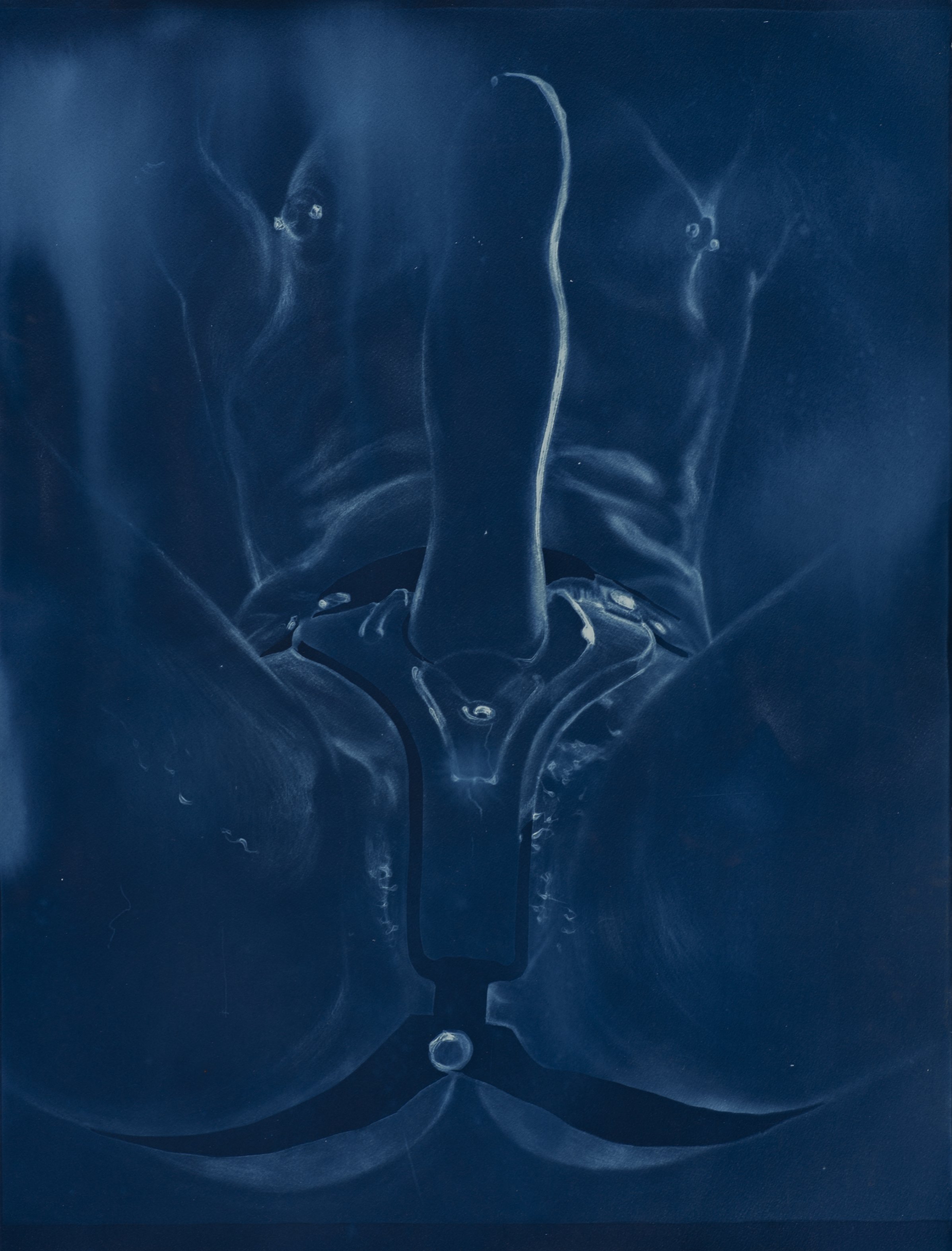

This is a cyanotype that I made in 2021, shortly after I started to explore this new medium in earnest. I was inspired to try cyanotype after learning about the 19th-century botanist and photographer Anna Adkins, a badass woman who is credited as the first person to publish a book illustrated with photographic images. I started by doing photograms of plant material and simple silhouettes but eventually (through much trial and error) I figured out a way to cyanotype my erotic drawings.

Hands can be such great vehicles for expression, and I wanted this image to be about self-pleasure. I work in batches when I do cyanotypes since I’m able to easily create multiples and I like to try different exposure times with the same image. I had no idea how this was going to turn out since it was my first time printing the image and my application of the solution was super irregular and watered down in areas. After exposing the paper for about 10 minutes in the sun, I rinsed it off in my bathtub and was pleasantly surprised by the placement of the faded streaks and the depth of blue. It’s still one of my favorite cyanotypes because I think it suggests more subtle mysteries like the inner world of the subject.

To me, this is what pleasure looks like.

6. What do your personal and artistic futures look like for you?

Mostly I just want to keep making art no matter what. Surviving under late-stage capitalism is a struggle and I have yet to reach a sustainable balance between making money and making art while also prioritizing my personal health and wellbeing. I hope to find a way to exist comfortably someday, but I also recognize that income inequality and our country’s lack of social safety nets are systemic issues that require radical social and political changes. It seems like the younger generations are much more eager to embrace the tenets of anarchy and democratic socialism, so maybe there is hope for us yet.

In the meantime- as the world continues to crumble and the climate goes berserk- I want to delve deeper into cyanotype, to push the medium into more complex compositions and onto different surfaces, like silk. I’m also excited to engage with mediums that are totally outside of my comfort zone, like ceramics. I want to explore more hand-building and sculptural wall pieces with intricate hand-painted sex scenes in cobalt glazes. I took a class at Studio Arts Boulder last year and one of my favorite pieces was a little square pinch pot I hand-painted with frogs fornicating on each side. While I remain committed to erotic themes, I’m also interested in weaving more animals and insects into my erotic art; de-centering the human to highlight the lives and mating rituals of the creatures we overlook. I took up mothing-the attraction, observation and documentation of moths- during the pandemic, and it’s become a hobby that I continue to draw artistic inspiration from.

I plan to continue teaching art because I think it’s important to share my skills and knowledge with others. There are very few spaces in this country that feel truly communal; so many public gatherings are tainted by capitalist motivations or religious dogma. Teaching art classes in non-academic settings has shown me that community can unfold through the collective experience of art-making. It can be extremely vulnerable to take an art class when it’s outside of your comfort zone, but I think that art is good for anyone who’s open to it.

Looking ahead, I would love to do an artist residency- to have the time and space to focus solely on my work. I would like to continue to show my art in physical spaces, whether locally or internationally. I still use platforms like Instagram to share my work, but with recent changes to its algorithms and the nauseating uptick in advertising, I’m much more inclined to seek out venues to exhibit in real life. Connecting with other artists and curators who get what I’m doing is so important, especially because erotic art is not readily embraced by a lot of institutions.

My long long-term goal is to live like the Slavic ogress Baba Yaga in an A-frame house on the beach in the upper peninsula of Michigan. I want to maintain an erotic lifestyle and do sexy cyanotypes on the beach in the summer. I’ll hunker down with my clutter of Siberian cats in the winter to make inks from foraged materials.

7. What influence do you hope to have on erotic art?

Personally, I like the idea of sex as a unifying language. When artists explore their own desires and sexuality without shame, I think it can inspire others to do the same. If I can contribute anything to the erotic art scene in Denver (and beyond) it’s an authentic expression of my desires and an invitation for others to center pleasure in their lives. I also want my work to get people talking about depictions of sex and pleasure in America.

A big part of what motivates me to engage with eroticism in my work is a personal disconnect with our dominant visual culture. In America, images of violence proliferative in mass media while depictions of nudity and sexual pleasure continue to be censored. This visual culture has resulted in an unfortunate narrowing of our collective imagination. Mainstream heteronormative pornography is generally focused on male pleasure and what looks good to the camera, rather than what feels good for all partners involved. I want to share stories and viewpoints that expand our conceptions of desire.

What does it mean to be an active subject in your erotic life, particularly in a culture with so many hang-ups around sex? How can we unpack personal or political beliefs that run counter to our sexual fantasies and desires? How can an artist create desire while complicating ideas around power? What distinguishes art from pornography, and what is the role of beauty in contemporary art? Finally, what does pleasure look like, especially when it’s not a performance? These are just some of the questions that guide my practice; starting points for the conversations that I want my work to open up.

Anything to plug?

You can view more of my work or contact me through Instagram(@ericapodwoiski) or my website podwoiski.com

And I’d like to take this opportunity to plug DILF (Damn I Love Frogs), an art show about frogs at dateline gallery that runs through November 25th!

I have an erotic frog planter in this ribbiting group show benefiting the Northern Colorado Herpetological Society.